“The Divine Emperor”… The Story of the Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire | Politics

In the spring of the first year of the twentieth century, Prince Hirohito was born in the Tokyo Palace, where his grandfather Mutsuhito, who was posthumously granted the title of Emperor Meiji, was reaping the fruits of his reforms and looking to expand the borders of his empire. The prince had not yet completed his fifth birthday when Japan had defeated Russia, expelled its forces from Korea, and become the greatest power in all of Asia and the dominant power in the Pacific region.

Hirohito grew up in imperial seclusion within the palace walls. When he was ten years old, his grandfather, Emperor Meiji, died. The young prince witnessed the ritual suicide of General Nogi Maresuke, the Japanese governor of Taiwan. The great general, at the age of sixty-two, did not hesitate to adhere to the ancient Shinto rules of servants following their masters in death. He and his wife committed suicide by stabbing them in the stomach with samurai swords, according to the hara-kiri ritual, especially after the general admitted to losing many of his soldiers in battle. This event may have impressed the young prince, and instilled in him a sense of pride in Shinto.

Yoshihito ascended the throne, and his son Hirohito became crown prince. He was raised to be austere, disciplined and respectful of Shinto rules, and received a modern education within the advanced educational system established by Emperor Meiji to catch up with the West. The crown prince was fond of biology, and is credited with discovering a new species of shrimp on the shores of Suruga Province, which was given a new name with imperial meaning, “Sympasiphae imperialis”. He also ordered the establishment and equipping of a laboratory for marine biology studies within the palace, and continued his research there until the end of his life.

When he reached the age of twenty, a reformist group of courtiers managed to convince the emperor and the courtiers to allow Crown Prince Hirohito to travel abroad, but the traditional group was terrified of violating court laws, as the imperial crown prince had never left the “land of the gods,” and the guardians of Shinto values threatened to commit suicide and throw themselves under the wheels of the train carrying the crown prince to his ship. But the young prince stuck to his guns and succeeded in traveling without bloodshed. His ship set off to visit several Asian stations, passing through Cairo and the Suez Canal. Then he began to discover Europe, which was busy clearing the rubble of World War I. He visited the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and the Vatican, and during six months he was given official receptions and royal banquets.

His journey outside the “Land of the Gods” was not without its own embarrassing moments for him and his companions. In Paris, he went shopping and discovered that he needed to handle money, but money was considered impure and was not to be touched by a descendant of the gods. In London, a long scroll from which he was reading his speech got tangled up, and the audience, who were not bound by Shinto rules, could not contain their laughter. And when the young crown prince insisted on trying to ride the London Underground incognito, his companions were horrified as they watched a clerk scold him for not having a ticket.

The crown prince returned to Japan with liberal ideas and a conviction that the barriers that kept him from the people were needed to be reduced, but opposition from the court limited his ambition. The following year, Hirohito became regent in place of his father, Yoshihito, who was suffering from mental illness. In late 1926, Yoshihito died, and Hirohito was crowned emperor at the age of twenty-five with lavish celebrations. He wore the ritual orange robes of his ancestors and made an offering of sacred rice at the shrine of his “grandmother,” the sun goddess.

Hirohito did not have the strength of character to monopolize power, and his court was sharply divided between the Westernization and traditionalism camps that had formed under his grandfather, Emperor Meiji. The first years of his reign witnessed attempts at rebellion in Korea, which gave the army leaders the opportunity to regain their influence at court in a manner reminiscent of what had been the case under the shogunate system. In 1931, they launched a new phase of colonial expansion with further penetration into Chinese territory and the occupation of Manchuria, then the invasion of northern China in 1937 and the entry into Beijing, Shanghai and the then capital Nanjing, with the aim of occupying all of China and thwarting its attempts to develop its army and economy.

In the summer of 1938, the Chinese resistance managed to repel the Japanese attacks and stop their advance. At the same time, the Japanese army leaders decided to invade the Soviet Union. Although they achieved some gains, the Mongolian and Soviet forces prevented the Japanese from penetrating Central Asia, so they decided to direct their ambitions towards the European colonies in the Pacific Ocean to seize them.

Hirohito did not object to the invasion of China, but some sources say that he was hesitant, and that the army leaders made him believe that the war would only last a few months. Western historians hold him responsible for the horrific massacres committed by his forces in China, and that he gave permission for the use of poison gas in hundreds of attacks during 1938.

While Japanese generals and admirals were making plans to expand into new territories and suppress rebels in their colonies, Hirohito lived quietly within the walls of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, writing poems calling for peace and harmony among nations, and occasionally engaging in his favorite pastime of studying biology and looking at tiny sea creatures under a microscope. He also occasionally rode his imperial procession through the streets near his palace, which prompted a Korean activist in early 1932 to attempt to assassinate him with a hand grenade, but the attempt did little harm.

The final war

In late 1936, Japan agreed with Germany and Italy to form the “Anti-Comintern Pact” to prevent the expansion of international communism, which naturally meant confronting the Soviet Union. After three years of tensions and struggle for influence between the major powers, German leader Adolf Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, sparking World War II. The field was quickly divided into two parties: the first was the “Axis”, which included Japan, Germany and Italy, countries looking to expand as much as possible to make up for what they had lost, and the second included the “Allies” of colonial countries – led by the United Kingdom and France – which had reached the peak of their expansion, before the United States later joined them.

During the war, Japan succeeded in occupying Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Singapore, and it also took control of the Indonesian oil fields, which was a heavy loss for Britain and its allies. Then came the fatal blow in late 1941 when the Japanese dared to target the American fleet in Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, a move that prompted the United States to emerge from its isolation and enter the war until the balance tipped in favor of the Allies.

Japanese propaganda presented the emperor to the people as a caring father who triumphed in all battles under the patronage of the gods. Even the army's withdrawals and successive losses in 1944 were interpreted as interim successes on the road to “certain victory.” However, the American targeting of Japanese shipping, the continued air raids on major cities, and the worsening food and housing crisis were enough to anger the people. The emperor decided to sacrifice Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and appoint two other prime ministers to continue the fight, but the Japanese loss in the war became more evident as time passed.

In mid-1944, the Japanese forces began implementing their most tragic plans in the war. After the dream of victory became close to impossible, the officers regained the samurai mentality and re-instilled it in the minds of their young pilots, so they launched their suicide planes under the slogan of “death with honor” with the aim of destroying the Allied ships. Thus began the phenomenon of “kamikaze” – meaning divine wind – which revived the legend of a storm sent by the spirits of the gods “Kami” on the fleets of the invading Mongols in the thirteenth century, destroying them. The souls of young Japanese were offered as a sacrifice for the land of the gods and the divine emperor.

Japan sacrificed more than 3,900 of its best young pilots in this suicidal phenomenon, and none of their attacks resulted in the sinking of any aircraft carrier, cruiser or battleship, as the sinking rate of ships exposed to these attacks was about 8%. Although the Japanese Navy succeeded in 1942 in sinking or disabling three American aircraft carriers without suicide operations.

In early 1945, the Emperor's advisers began trying to persuade him to negotiate an end to the war, to no avail. In May, Germany surrendered and Hitler committed suicide. The Italian leader, Benito Mussolini, had been killed by the revolutionaries a few days earlier, leaving Hirohito alone in the field. Nevertheless, he insisted on fighting to the last man, but continuing pressure from within the court led him in June to accept negotiations with the Soviets on a formula for peace.

Japanese society was in an unprecedented state of disintegration, with threats of a communist revolution to overthrow the imperial throne, and other threats from fanatical Shintoists of mass suicide and their preference for death over the shame of surrender. As for Hirohito, he stipulated in all his negotiations the preservation of the system of government called “Kokutai”, which includes imperial rule, the constitution, and the identity of the state.

Meanwhile, the United States and its allies were planning Operation Olympic, a massive invasion of Japan that was expected to kill millions more people on all sides. As a prelude to the operation, Tokyo was incendiary bombed in March, killing an estimated 100,000 people in two days. By mid-June, Japan’s six largest cities were in ruins. Then came the final blow on August 6, when the United States dropped its first atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

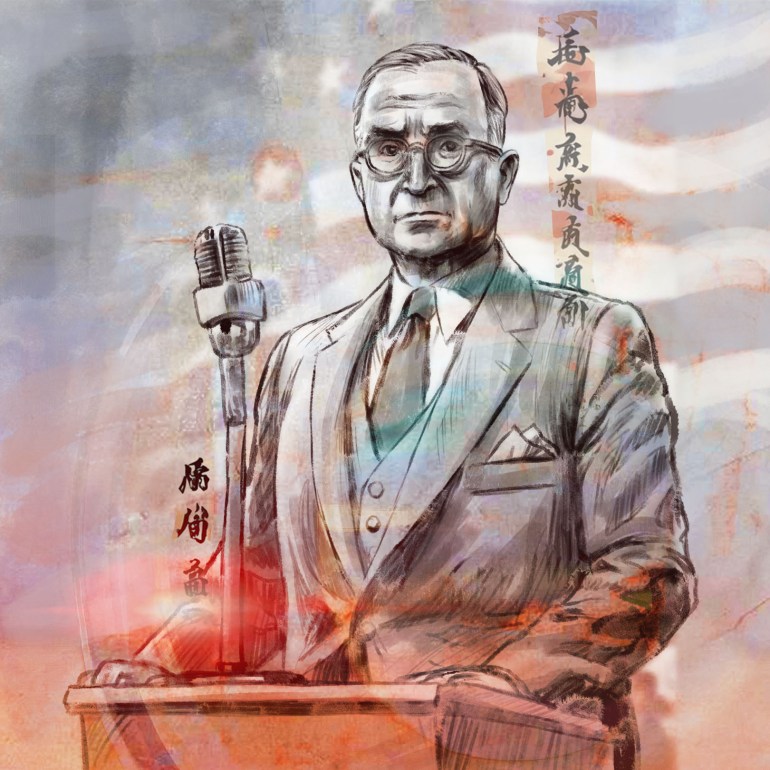

The city was obliterated within minutes, and US President Harry Truman made a broadcast around the world threatening the Japanese with an unprecedented torrent of destruction if they did not accept the Allied terms, followed by a sea and land invasion of the country. Japan, however, insisted on fighting on, urging its citizens by radio to evacuate major cities and informing them that Hiroshima had already been destroyed by a single bomb. At midnight on August 9, Soviet forces launched the Manchurian Strategic Offensive to seize Manchuria, formally declaring war on Japan, even though the two countries had been bound by a neutrality pact throughout the war. Just a few hours later, an American aircraft dropped another atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki.

Over the next three days, the United States prepared another atomic bomb for use, which was to be dropped over an uninhabited area. The plan was to have three more bombs ready in September and three more in October, and to launch Operation Olympic to invade Japan that same month. However, during these days, Japanese officials continued to meet to decide on the surrender formula. On August 12, Hirohito informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. When one of the princes asked him if the war would continue if the enemies did not accept the preservation of the “kokutai”, Hirohito replied: “Of course,” as if he was prepared to sacrifice the rest of the people in order to preserve the throne and the government.

Two days later, Hirohito delivered his surrender speech on the radio. He did not mention the word “surrender”, but said that he had decided to accept the terms of the “Joint Declaration of the Allied Powers,” explaining that the enemy had begun to use a new bomb of uncalculated power, and that continuing to fight would lead not only to the collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also to the complete extinction of human civilization. Due to the poor quality of the broadcast and the Emperor's choice of formal language, the public was confused, and the radio announced clearly that Japan accepted surrender unconditionally.

Five days later, Hirohito gave a speech to the soldiers, in which he made no mention of the atomic bombs, but justified the surrender by citing the Soviet declaration of war, which he described as “endangering the existence of the empire.”

The Japanese people's reactions to the surrender varied. There was a failed coup attempt, and some army and navy officers chose to commit suicide in the Shinto way because they found it difficult to accept the idea of surrender. A small crowd gathered in front of the Imperial Palace to cry, while many people hid their feelings of grief and anger at the loss of all the enormous sacrifices they had made. Their country emerged from this war in a state of total destruction, losing all its overseas colonies, and achieving no significant gains. As for the masses of the Allied countries, they received the news of Japan's surrender with huge celebrations, and pictures and banners were raised in their destroyed streets to embody the victory. The date of August 14 was adopted as a day to celebrate the anniversary of the victory over Japan in some countries.

On August 19, Japanese officials traveled to Manila to meet with the Supreme Allied Commander, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, and learn his plans for occupying Japan under the terms of surrender. On August 28, the U.S. occupation of Japan began, and two days later MacArthur arrived in Tokyo and ordered Allied troops not to attack the Japanese people and were not to approach the people's food sources.

On the morning of September 2, the deck of the USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay, witnessed the signing of the instrument of surrender by Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu and Army Commander General Yoshihiro Umezu, with some Japanese officers shedding tears as they watched silently.