ChatGPT's language bias: Three ways it's leaving non-English speakers behind – BBC News

- Joe Tidy

- BBC reporter

Image source,Getty Images

Non-English speakers around the world are being left behind because artificial intelligence (AI) systems are biased towards English, experts have warned.

AI-generated tools like ChatGPT and Google Bard are bringing new skills and business ideas to millions of people, but they also have the potential to leave many more vulnerable.

In the past few months, companies, often backed by the government, have raced to launch or begin building AI for their native languages, including Indonesian, Japanese, Chinese, Korean and multiple languages in India.

But can they rival Silicon Valley’s AI robots, or offer a credible alternative?

Here are three ways non-English speakers are being left behind by generative AI, and why we need to take this issue seriously.

1. Lower accuracy and higher cost for non-English speakers

Machine learning engineer Yennie Jun began to notice this problem when she was testing ChatGPT-4 in different languages.

“I found it was a lot slower and didn’t work as well as with Korean and Chinese, which usually have high-quality training data available,” she said.

Earlier this month, Zhenni Cheng decided to test OpenAI’s latest artificial intelligence model, GPT-4, with some tricky math problems.

Image source,Getty Images

She posed the same math problems in 16 different languages and found that GPT-4 performed better at solving problems in certain languages, such as English, German, and Spanish.

In fact, GPT-4 was three times more likely to correctly solve math problems posed to it in English than in other languages, such as Armenian or Farsi. It was unable to solve any difficult problems posed to it in Burmese or Amharic.

This is just the latest experiment Cheng has conducted to highlight the inequality of ChatGPT and other so-called AI “large language models.”

In another test earlier this summer, Cheng created a “Tokenizer” tool to illustrate why these AI models struggle with non-English languages.

The AI breaks sentences into smaller, more understandable chunks, called “tokens.” The less it understands the language, the more tokens it creates. For example, if you type the simple sentence “tell me about morel mushrooms” into her tokenizer tool in different languages, the number of tokens will vary greatly:

- English: 6 words

- Spanish: 8 words

- Chinese (Mandarin): 14 syllables

- Burmese: 65 words

This is important because it means that non-English users will be slightly slower to get results, and they won’t be able to type as many words into the tooltip as English users can because the tooltip is limited by word length.

But Cheng said the real disadvantage of this inequality comes from companies trying to use these AIs to build products and services.

For example, if a mushroom farming business built ChatGPT-4 into its app to answer customer questions, it would cost the company 10 times more to serve Burmese customers than English-speaking customers because of the large number of words required to answer customer requests.

This isn’t specific to ChatGPT, all large language models have similar discrepancies, and Google’s Bard acknowledges this when you ask it about this: “Bard’s tokenization of non-English languages may result in slower and more expensive hints in other languages, as the tokenization process for non-English languages is much more complex than English.”

2. English-first AI fails to reflect other cultures

Image source,EPA

English dominates the internet and now dominates artificial intelligence.

The reason behind this is that most AI models are trained using data collected from the open source internet, and the vast majority of this data is in English.

The nonprofit Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) pointed out in its report on AI language bias that although only 16% of the world's population speaks English, English websites account for 63.7% of the world's websites.

English is often described as a “rich” language, with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of texts, from social media posts to business reports and scientific papers.

However, the richness of a language's online resources is not proportional to the number of its users.

For example, researchers at the Center for Democracy and Technology said that despite the continent having more than 600 million internet users, almost all African languages remain “low-resource” languages.

There are different ways of classifying languages in academia, but here is a general overview of the state of language resources:

- Language with the most resources: English

- Languages with many resources: Chinese (Mandarin), Japanese, Spanish, German, French, Russian, Arabic

- Medium-resource languages: Hindi, Portuguese, Vietnamese, Dutch, Korean, Indonesian, Finnish, Polish, Czech

- Low-resource languages: Basque, Haitian Creole, Swahili, Amharic, Burmese, Cherokee, Zulu, and most other languages

OpenAI does not disclose the percentage of English in ChatGPT's training data. If you ask AI, its response is “the specific classification and percentage of languages in the dataset remains proprietary information.” When asked about this information, Google's Bard also said that the specific data samples are “confidential.”

As the Center for Democracy and Technology said in its report, “This bias fails to reflect the diversity of languages used by internet users around the world and further perpetuates the dominance of English.”

Zheng Zhenni said her experiments also found a strong Western bias.

“I did some experiments, like asking AI about important events and figures in history, and even if you ask in other languages, it still comes up with very Western-biased figures and events,” she said.

3. Silicon Valley may not solve inequality

Image source,Getty Images

The Center for Democracy and Technology argues that US companies are not investing as much money in improving the experience for non-English speaking customers because less revenue is generated from regions such as the Global South.

As first reported by Wired, an OpenAI employee admitted in a developer forum last year that the company’s models were “intentionally trained in English” and that “any good results in Spanish are a bonus.”

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, who was questioned at a hearing before a U.S. Senate committee about the tool's bias toward English speakers, said the company was “equally concerned” about ensuring other cultures were included.

Neither OpenAI nor Google responded to questions we sent to their press offices.

Another AI giant, Meta, is investing in a large translation project called No Language Left Behind to improve machine learning translation tools for hundreds of languages. But even so, the company admitted that its latest large language model, Llama 2, is “still fragile for non-English users and should be used with caution.”

Nick Adams, founding partner of AI-focused venture capital fund Differential Ventures, said if the status quo continues, money and investment will continue to flow to already wealthy companies, countries and languages.

“I think the current state of AI will accelerate inequality rather than make it better. Emerging markets don’t have the computing power, data sets or financial resources required for AI to compete with the Western world’s models,” he said.

In addition to the lack of investment in non-English AI, the data problem is difficult to overcome and even beyond the capabilities of US tech giants.

It was once thought that developing multilingual language models could solve the data gap problem by training AI models to discover patterns in high-resource languages and applying them to lower-resource languages. But some, including the Center for Democracy and Technology and other researchers, argue that multilingual language models still perform poorly for non-English speakers.

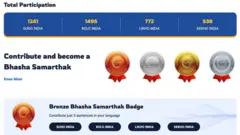

Image source,Bhasha Daan Initiative

India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology has launched an ambitious project to increase the amount of training data for low-resource languages through crowdsourcing.

The Bhasha Daan initiative invites people to “improve their AI language models by validating data.” The program plays podcasts or show audio in different Indian languages to participants, then gives them digital medals for translating it into their own language.

However, this approach still has a long way to go. Despite the large native speaker population, only a few thousand people have participated so far.